They say that music can drive you mad! A force that can impact emotions and mental conditions, over a period of time or very suddenly as well. Forms of pop-music can send teenagers into howling fits or an old etude can bring a listener to tears. A song from 'back then' can give you the goosebumps and a melody can transcend you back in time. Sometimes it takes just a few notes to trigger specific neurotransmitters in our brain, which consequently create feelings and reactions, which are definitely beyond normal. Beyond the cultural and social relevance of music, there lies a vast space of emotional and psychological value connected to music. Sound and music provide unique emotional experiences, that takes on personal and psychological meaning in end. The end being our consciousness. New research and care-giving practices are revealing that music (and sound) can play an important role in improving memory, cognition and overall mental health. What's even more fascinating is that music has positively impacted people suffering from dementia, bi-polar disorder and Alzheimers. The article takes a brief account of how music effects various cognitive capacities in the brain and how care-giving practitioners are encouraged by the impact of music on our mind.

Music and memory have a mysterious multi-layered relationship. Much has been written about it from a cultural and historical context, yet the psychological domain remained unexplored - an emerging realm of healing and discussion as we speak. Take for example the research and experiments conducted by Theresa Allison (University of California) in the field of dementia, aging and care-giving via music. "We found that when patients have access to preferred forms of music, at home or in a hospital, they need fewer anti-depressants and anti-psychotic medication. The effect of singing (by care-givers) also has an enhancing effect on the patient, when compared to talking and conversation..." says Theresa Allison in a recent lecture. Interestingly, the response to music is preserved, the likeness and reaction to music, even when the dementia and Alzheimers is advanced. Even when patients have impairment of executive functions (judgment, general reasoning), speech, and language - their ability to recall or cognitive abilities respond with music. By no means is the process instantaneous, and there are no magic pieces.

The emerging practices are still in formation, as research points to the time needed, for music to be able to initiate the rewiring, or re-connection between various faculties of the brain. The emergence of music as therapy for mental disorders has just about begun to pose a challenge for the pharmaceutical industry. "The positive impact of music over time on the patients of dementia, also raises an important question - did they need all the medication in the first place?" asks Theresa Allison. The question points to a breakthrough of sorts. Given the many known (and unknown) adverse effects of anti-depressants and anti-psychotic medicines on our mind and body - in comparison music as therapy has no such repercussions.

"The power of music, especially singing, that can unlock memories and kickstart the grey matter, is an emerging key feature of dementia care. Music seems to reach parts of the damaged brain in ways other forms of communication cannot..." states a recent article in Aging.org. Our connection with music, which starts very early as a baby, remains active throughout our lives, yet in certain ways dormant. We know well, that listening to music, depending if we are in a group or alone, can be two very distinct experiences. Neurological research has shown that we tend to "remain contactable as musical beings" on some level right up to the very end of life. Perhaps a lifetime of sound is retained within us as trigger points. We are missing the switches? "We know that the auditory system of the brain is the first to fully function (a newborn of 3 to 4 months), which means that you are musically receptive long before anything else. So it’s a case of first in, last out when it comes to breakdown of memory..." states a new article in Practical Neurology.

In his famous book Musicology (2007) Oliver Sacks discussed a few patients with severe memory impairment. In particular, the English musician Clive Wearing, who developed Herpes Encephalitis in his early 40s. Oliver Sacks concluded that the patient when hearing 'Prelude 9 in E major' remembered playing it before. With this specific music, he was able to improvise, joke, and play any piece of music. His general knowledge or semantic memory was also positively effected. This is not say that western classical music is the key to improving memory for such conditions - yet the impact of music depending on the person's background and history has a undeniable link with animating neurotransmitters, which were previously thought to be dead or inaccessible.

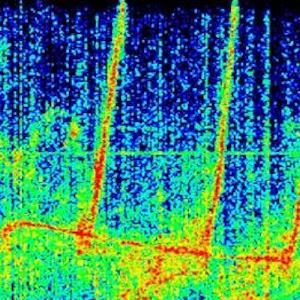

"The impact of preferred music, based on the patient's background, over time

has shown clear signs of improvement - be it on the ability to recall

(memory) or the reduction of stress, agitation (temporal mood and

behavior). What's most encouraging is the effect of live singing or

playing the guitar, to which a large number of patients have shown a

marked increase in their ability to perform everyday functions..." states Erik Kandel, Nobel Prize winner in Medicine. Music can have a significant impact on memory and cognition beyond

merely enjoying and listening to it. The 'action and exchange' between the synapses and transmitters is something we may never be able to understand completely. Those who make music, unconsciously wire their brains differently. Musicians seem to hold a

"greater volume" of the auditory cortex and anterior 'corpus

callosum' compared to non-musicians.

Musicians are likely to recruit both halves of the brain when performing

musical tasks (such as detection of pitch, time divisions, melody etc).

Studies have shown

that elderly musicians outperform non-musicians, when assessing

auditory processing, cognitive control, and comprehension of speech in

noisy environments. The auditory processing can also regress and

deteriorate when exposed to long periods of very loud volume (concerts,

clubs etc).

One must consider that the effect of music on patients of dementia, bi-polar disorder and alzheimers is still temporal. The instinct and intellect behind music, let alone the vast complexity of the human brain are two universes, asking for more exploration. The two questions we are left wondering - What kind of music? What type of transmission? Majority of the research and results are based on simple forms of music - usually played on a piano or acoustic guitar. There have been instances of complex orchestral music and on rare instances "golden oldies" too. Yet one is encouraged to experiment with any sort of music and sounds, as long as it's "preferred" - something that the patient and caregiver can relate to.

The transmission of voice, of notes,

melodies or even complex polyphonic music are all part of applied

practices. Singing seems the preferred way for a majority as of now. Recorded or prepared or straight up live. The

impact of music from childhood, be it instrumental or vocal has proven

to a be preferred idea by caregivers. Once any music is part of us, it

seldom takes its leave. To recall the story from Oliver Sack's book - about the guy suffering from Alzheimers, who had no idea what he did

for a

living or for that matter what happened 10 minutes ago, but

remembered well the melody to almost every song he had ever sung... With instinct, we can say that

no one can placate what music creates within our mind, does to us,

regardless of us being common, prodigious or demented. Healing with music and less with with prescription pills!

0 -